Computer Architecture

Lab1

Tools

How to compile assembler files?

-

First we need to assemble the output.

as -g --32 <SRC_PATH> -o <HALF_OUTPUT_PATH>- -g - generate debugging information

- --32 - use 32bit architecture

- <SRC_PATH> - source file with code (.S file)

- -o <HALF_OUTPUT_PATH> - assembly output (.o file)

-

Then we need to use linker

ld -m elf_i386 <HALF_OUTPUT_PATH> -o <FINAL_OUTPUT_PATH>- -m elf_i386 - select emulation for 32bit architecture

- <HALF_OUTPUT_PATH> - assembly output (.o file)

- -o <FINAL_OUTPUT_PATH> - final program output

-

Now you should be able to execute the program. (./<FINAL_OUTPUT_PATH>)

Debugger

As we are not printing out anything in most cases we need some way to see what is hapenning in the program.

That's where debugger comes to rescue. On Linux we can use gdb.

gdb --tui ./<FINAL_OUTPUT_PATH>Basic commands:

- run - execute program from start (stop on breakpoints)

- layout regs - show window with register values

- continue - continue program execution

- break | br | b - insert breakpoint (ex. br line 5, br _start)

- quit - quit the program

Program Structure

Basic code structure we will use 99% of the time:

.section .text

.globl _start

_start:

# Some code

# Program exit

mov $0, %EBX # return code

mov $1, %EAX

int $0x80 # system call exit

ADD and SUB(tract)

Adding two values:

add A, B is equivalent to B += A

Subtracting two values:

sub A, B is equivalent to B -= A

.globl _start| Register | Value |

|---|---|

| EAX | ? |

| EBX | ? |

| ECX | ? |

| EDX | ? |

mov $2, %EBXMove literal 2 to EBX register. (EBX = 2)

| Register | Value |

|---|---|

| EAX | ? |

| EBX | 2 |

| ECX | ? |

| EDX | ? |

mov $1, %EDXMove literal 1 to EBX register. (EDX = 1)

| Register | Value |

|---|---|

| EAX | ? |

| EBX | 2 |

| ECX | ? |

| EDX | 1 |

mov $10, %ECXMove literal 10 to ECX register. (EDX = 10)

| Register | Value |

|---|---|

| EAX | ? |

| EBX | 2 |

| ECX | 10 |

| EDX | 1 |

add %EDX, %EBXAdd EDX to EBX. (EBX += EDX | EBX = 2 + 1)

| Register | Value |

|---|---|

| EAX | 7 |

| EBX | 3 |

| ECX | 10 |

| EDX | 1 |

sub %EBX, %ECXSubtract ECX from EDX. (ECX -= EDX | ECX = 10 - 3)

| Register | Value |

|---|---|

| EAX | ? |

| EBX | 3 |

| ECX | 7 |

| EDX | 1 |

mov %ECX, %EAXMove ECX value to EAX register. (EAX = ECX | EAX = 7)

| Register | Value |

|---|---|

| EAX | 7 |

| EBX | 3 |

| ECX | 7 |

| EDX | 1 |

nopnop - no operation - end of program

| Register | Value |

|---|---|

| EAX | 7 |

| EBX | 3 |

| ECX | 7 |

| EDX | 1 |

MUL(tiply)

Multiplying two values:

mul A is NOT so simple as it will always give us 64bit value (in 32bit architecture)

Example 4x3 will look like this:

| 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000100 | = 4 | |

| x | 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000011 | = 3 |

| ----------------------------------- | ||

| 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 | 00000000 00000000 00000000 00001100 | = 12 |

| | | | | |

| \/ | \/ | |

| EDX | EAX |

mov %EDX, %EAX EAX = EDX (EAX = 4)

mul %EBX EBX * EAX = 4 * 3 - result is pushed into EDX and EAX

mov %EAX, %ECX ECX = EAX (ECX = 12)

DIV(ide)

Dividing two values:

div A is NOT so simple as it will always give us two 32bit values - EAX (quotient) and EDX (remainder) (in 32bit architecture)

Example 12/4 will look like this:

| 00000000 00000000 00000000 00001100 | <- EAX = 12 | |

| / | 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000100 | <- given variable = 4 |

| ----------------------------------- | ||

| 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000011 | 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 | |

| | | | | |

| quotient | remainder | |

| \/ | \/ | |

| EAX = 3 | EDX = 0 |

mov %EBX, %EAX EAX = EBX (EAX = 12)

mov %EDX, %EBX EBX = EDX (EBX = 3)

mov $0, %EDX IMPORTANT! EDX must be zero

div %EBX EAX / EBX (12/3) - result is pushed into EAX (quotient) and EDX (remainder)

mov %EAX, %ECX ECX = EAX (ECX = 4)

Logic Gates

AND

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| - | - | - | - |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

OR

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| - | - | - | - |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

XOR

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| - | - | - | - |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

NAND

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| - | - | - | - |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

NOR

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| - | - | - | - |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

XNOR

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| - | - | - | - |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

6 basic gates on 1bit values are simple, BUT we use those operators on 32bit values.

That means when using any of those instructions we change every bit.

Example AND %EAX, %EBX where EAX = 15 EBX = 9

| 00000000 00000000 00000000 00001001 | = 9 | |

| AND | 00000000 00000000 00000000 00001111 | = 15 |

| ----------------------------------- | ||

| 00000000 00000000 00000000 00001001 | = 9 | |

| | | ||

| \/ | ||

| EBX = 9 |

We can use 16bit values

Example AND %AX, %BX where AX = 15 BX = 9

| 00000000 00001001 | = 9 | |

| OR | 00000000 00001111 | = 15 |

| ----------------- | ||

| 00000000 00001111 | = 15 | |

| | | ||

| \/ | ||

| BX = 9 |

or even 8bit values

Example AND %AL, %AH where AL = 15 AH = 9

| 00001001 | = 9 | |

| OR | 00001111 | = 15 |

| -------- | ||

| 00001111 | = 15 | |

| | | ||

| \/ | ||

| AH = 9 |

(e)XCH(an)G(e)

Exchange values

xchg %EAX, %EBX EAX = 3, EBX = 12

INC(rease) and DEC(rease)

INC can be understood as var++

DEC can be understood as var--

Lab 2 & Lab 3

C(o)MP(are)

Using compare is tricky with AT&T syntax.

Example CMP %EAX, %EBX

It should be read as EBX ? EAX where ? can be exchanged by:

- == - EBX is equal to EAX

- != - EBX is not equal to EAX

- > - EBX is greater than EAX

- >= - EBX is greater than or equal to EAX

- < - EBX is less than EAX

- <= - EBX is less or equal to EAX

J(u)MP

Basic usage: JMP DESTINATION

Will change where the processor should look for next operation. Thinking abstractly about it - change cursor position.

Tightly connected with CMP command jump command have multiple comparison options:

- == - je - Jump if Equal

- != - jne - Jump if Not Equal

- > - jg - Jump if Greater (jnle - Jump If Not Less or Even)

- >= - jge - Jump if Greater or Even (jnl - Jump if Not Less)

- < - jl - Jump if Less (jnge - Jump If Not Greater or Even)

- <= - jle - Jump if Less or Even (jng - Jump if Not Greater)

Lab 4

Array

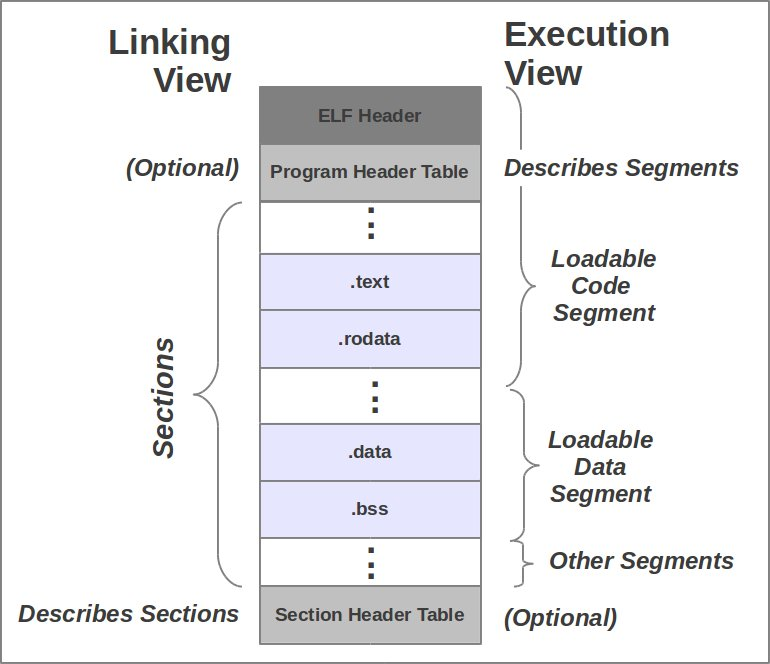

For understanding arrays it is recommended to know where we can allocate data

For our usage we are interested in .data and .bss sections

- .data - can be understood as internal RAM

- .bss - can be understood as internal RAM that is unitialized

How to address an array?

Example -4(%ebx, %ecx, 4) (every register can be used to do it not only %ebx and %ecx)

-4 - displacement (usually the size of the array or one value)

%ebx - base register (usually start or end of the array)

%ecx - index

4 - scale factor (usually the size of the value)

And the whole thing can be represented as mathematic formula -4 + EBX + (ECX * 4)

Side note: Brackets '()' are changing how the processor is looking at numbers (as pointers and not as values)

See that literal numbers are not preceded by $

Example table tab[0] = 5; tab[1] = 8; tab[2] = 7; tab[11] = 11;

EBX is pointing at the end of the table and ECX is equal 0